16th August, 2021

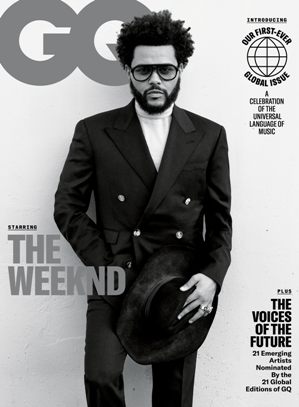

16th August, 2021In a new cover story for GQ’s September issue, the brand’s first-ever global edition, singer The Weeknd, also known as Abel Tesfaye, speaks with special projects editor Mark Anthony Green about his upcoming album, The Grammys, and how he separates Abel from his dark, gritty public persona.

Abel and The Weeknd are two very different beings. The Weeknd has the longest-charting song by a solo artist in history and billions of worldwide streams. The Weeknd spent his pandemic in a red blazer licking frogs dipped in LSD. Abel, meanwhile, was bingeing The X-Files.

“The lines [between Abel and The Weeknd] were blurry at the beginning,” says Abel. “And as my career developed as I developed as a man it’s become very clear that Abel is someone I go home to every night. And The Weeknd is someone I go to work as.”

When ‘House of Balloons’was released in 2011, The Weeknd was anonymous.

”I feel like with me it’s never been about the artist and the image of the artist,” Abel says. “With House of Balloons, nobody knew what I looked like. And I felt like it was the most unbiased reaction you can get to the music, because you couldn’t put a face to it. Especially R&B, which is a genre that is heavily influenced by how the artist looks.”

It was during this anonymous period that Abel’s single What You Need was released, and he heard it played for the first time in a public setting.

“I was struggling at the time. A good friend of mine hooked me up with a job at American Apparel, and I was folding clothes there when somebody at the store played the song,” he says. “Mind you, nobody knew who The Weeknd was. I started listening, seeing what people thought of it. That’s what I mean by the unbiased reaction. When I saw that everybody was like, “This is fire,” I was like, “Oh!”

Abel grew up in a multicultural neighbourhood, which had a vibrant Indian community and signed a very talented Punjabi-Canadian rapper, Nav, to his XO label. What are some aspects of India, Indian culture that he enjoys?“Well, it's very similar to African culture. The celebrations are big. The weddings are big. The families are big, and the families are close. The first thing I realized when I hung out with Nav a lot, is a lot of his culture is very similar to my culture. And we related to that a lot, so I relate to Indian culture.”

Abel shares some of his upcoming project with GQ, which describes them as “Quincy Jones meets Giorgio Moroder meets the best-night-of-your- fucking-life party records. Not anachronistic disco stuff. (Not “cosplay,” as Abel put it.) Sweaty. Hard. Drenched-suit, grinding-on- the-girl/boy-of-your-dreams party records.”

“It’s the album I’ve always wanted to make,” says Abel. And his success won’t necessarily be quantified by streaming numbers and record sales.

“What makes any of my albums a successful album, especially this one, is me putting it out and getting excited to make the next one,” he says. “So the excitement to make the next project means that this one was successful to me. I want to do this forever. And even if I start getting into different mediums and different types of expressions, music will be right there. I’m not going to step away from it.”

Reflecting on past projects, Abel is certain he’s made his best work when he’s been sad.

“I believe that when anybody is sad, they make better music,” he says. “And I’ve definitely been a victim of wanting to be sad for that, because I’m very aware. I definitely put myself in situations where it’s psychologically self-harming. Because making great music is a drug. It’s an addiction and you want to always have that. Fortunately, I’ve been through that and I’ve learned how to channel it. And I’ve experienced enough darkness in my life for a lifetime. I feel lucky that I have music, and that’s probably why I haven’t dabbled into too much therapy, because I feel like music has been my therapy.”

Last November, The Weeknd called the Grammys “corrupt” when ‘After Hours’, which hit No. 1 on the Billboard charts and went platinum multiple times over, wasn’t nominated in a single category. The snub felt like an odd deviation from the organization’s usual formula, in which critical acclaim plus commercial success equals a ton of nominations, and he vowed to boycott the Grammys altogether going forward.

“When it happened, I had all these ideas and thoughts,” he says. “I was angry and I was confused and I was sad. But now, looking back at it, I never want to know what really happened.”

When asked whether he plans to submit his music to the Grammys ever again he says, “I have no interest. Everyone’s like, ‘No, just do better next time.’ I will do better, but not for you. I’m going to do better for me.”

Read “The Weeknd vs. Abel Tesfaye” by Mark Anthony Green in GQ’s September issue and on gqindia.com

Courtesy: GQ Magazine.