16th September, 2015

16th September, 2015Tanuja Desai Hidier is a writer/singer-songwriter, born and raised in the USA and now based in London. Her first novel, ‘Born Confused’, the first ever South Asian American coming-of-age story, set in the context of New York City’s bhangra/underground club scene was held in high esteem leaving a lasting impression on anyone who read it. Hidier took on the role of musician when she released ‘When we were Twins’ an album of original songs based on ‘Born Confused’. It was featured in Wired Magazine for being a first-ever booktrack;

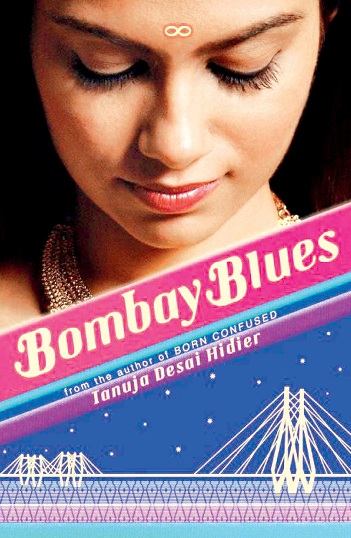

Her second novel, ’Bombay Blues’ the sequel to ‘Born Confused’ was released in August this year along with her new ‘booktrack’Bombay Spleen, her album of original songs based on Bombay Blues, which is available worldwide. Featuring twelve tracks of infectious electro-dream-pop ‘wreckage rock’, the album is produced by Dave Sharma, with special musical guests world-renowned trumpet player Jon Faddis and bassist Gaurav Vaz (of The Raghu Dixit Project).

Bombay Spleen draws from the themes of Bombay Blues, love, home, cultural history, and the mapping / unmapping of identity, with the musical narrator’s personal journey paralleling that of Dimple’s, as well as that of Bombay’s development itself: from its beginnings as seven islands later reclaimed to become the city we know today. The track Seek me in the Strange, has been selected for the soundtrack of director Liz Hinlein’s feature film Other People’s Children. Deep Blue She was selected for the #VogueEmpower playlist for Vogue Fest 2014 (Vogue India’s social awareness initiative for women).

The first music video for the album (for the track Heptanesia directed by Tim Cunningham) is out now. The song is currently airing on MTV India (Pepsi-MTV Indies).

Tanuja has also collaborated with Asian Underground legend State of Bengal (Björk, Massive Attack, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Cheb i Sabbah).

Tanuja shares her story in an exhaustive interview. Sit back and enjoy reading.

You recently released your single Heptanesia on MTV Indies. What is the song all about?

“Heptanesia” is the first release from Bombay Spleen—my ‘booktrack’ album of original songs based on my second novel Bombay Blues. The album title is a reference to Baudelaire’s Paris Spleen-—his prose-poem to Paris, which my protagonist, Indian-American photographer Dimple Lala is reading when the story opens. And Bombay Blues/Spleen are kind of my prose-poem to Bombay—a city I’d only lived in as a baby, but a literal motherland: My mother was Vile Parle born and raised; my parents met in med school in Parel; my brother was born near Marine Lines. Heptanesia is the earliest documented name for the islands that were Bombay, from the ancient Greek for ‘cluster of seven islands’. When I discovered this term along my researching way, I knew I just had to use it, in both my novel and album. Such a mysterious, poetic, nostalgic term—yet so official sounding, authoritatively evident: like a secret clasped in your own very hand. The word immediately evoked ideas of amnesia, anesthesia, synesthesia. Remembering, forgetting—and the feeling too much that can lead to this—and the thin line, the bridge, really, between truth and fiction. These are all themes in the “Heptanesia” chapter of Bombay Blues too, both in terms of the protagonist’s dynamic with Bombay as well as in a personal relationship. It felt fitting, necessary that a take on this semi-mythical place be a part of my book and album—as the city that Dimple (and I) were seeking a connection to in Bombay (the term that to me/her connotes a link to family history), Mumbai (the modern-day metropolis), and Unbombay (a fictitious zone that she unexpectedly discovers when she drops the map) is in many ways semi-mythical: a space of memory, aspiration, imagination—yet one at least as real as the dust between your toes from little lane below your feet. Heptanesia for me is the before the ‘before’, one that goes so far back it’s full-circle here again: a space where the past, present, future dreamlike meet. I wrote “Heptanesia” with London/Ghent-based Marie Tueje (I wrote about half of Bombay Spleen with her, the other with NYC’s Atom Fellows). It was produced by Dave Sharma in Brooklyn and features the lovely legendary Jon Faddis on mute trumpet, and warm wonderful Neel Murgai on sitar. And no less a part of team Spleen: “Heptanesia” music video director Tim Cunningham (whom I’d met in an intensive filmmaking course years ago in New York—sweating profusely as we lugged gear around Union Square that summer, we vowed then to make something together one day…and at last it happened). For the music video, the idea was to go for a torch-singer-with-Bollywood-and-Ingmar Bergman’s Persona-touch look/feel—an older-era vibe mixed with present-day Bombay footage (converging an old/new city in a time warp, as happens in the song and book). There are some visual references to the Wizard of Oz too (a book theme/chapter is “Home is Not a Place”, another take on ‘there’s no place like home’). Tim directed, shot, and edited the video here in London. Additional Bombay footage was shot by ace Bombay-based filmmaker Shanker Raman. The video also includes some of the footage I took in Bombay during my research trips while taking visual notes for Bombay Blues (for example, one time crossing the Sea Link Bridge—which is almost like a character, and definitely a muse, in Bombay Blues--I just held my camera up to the window a few seconds to remember the phantom-ship feel of the structure; this shot ended up interspersed through the video).

You are also releasing a book - Bombay Blues. What does the book talk about and who is it directed to?

Bombay Blues--the novel upon which the songs on my album Bombay Spleenare based-- is the sequel to my first novel Born Confused (which has just been re-released in a new edition along with Bombay Blues). A little background: Set in the context of New York City’s bhangra / underground club scene during the summer aspiring photographer Dimple Lala turns seventeen, the heart of Born Confused is about learning how to bring two cultures together without falling apart yourself in the process. (The book takes its title from ABCD, or American Born Confused Desi, a term used to describe these second and third generation South Asians who are supposedly “confused” about where their roots lie). With Born Confused, I was interested in exploring in part the idea of what happens when a subculture gains critical mass and momentum to become culture. And I wanted to pay homage to the thrilling then burgeoning bhangra/South Asian club scene in New York City, one inextricably linked to the amazing cultural moment in music out of the UK in ’97 (with the so-called ‘Asian Underground’ movement). In NYC it was DJ Rekha’s Basement Bhangra party –still going strong after seventeen years — and Mutiny at the Cooler that in many ways sparked the desire to tell the story of this cultural moment. It was an eye- and ear-opening experience living it. Through Dimple, I wanted to turn the ‘C’ for Confused into one for Creative in American Born Confused Desi — as this felt to me to more accurately reflect the desis that peopled the world I’d known in NYC. With Bombay Blues, it was a completely different story. I’d only lived in Bombay for about a year shortly after birth; I’d visited a few times in my childhood, mostly staying with my grandparents. The city was a mystery — but still felt like a mystery in my blood, quite literally, as it’s the city of my family history. I was driven by a desire and a duty, in a sense — to better know the city of my parents, and create my own connection to it. Find an ‘in’. Bombay Blues sees heroine Dimple Lala journey from NYC to India. Set against the backdrop of Mumbai’s contemporary indie music and arts scene, the book explores what this generation of young adults faces today — and the dynamic between a modern-day globalized Bombay, including the expat culture (reverse diaspora) that is a significant part of it, and its more ancient and traditional self. With Bombay Blues, I also wanted to move beyond questions of culture, or at least that kind of framework. To step out of frame: enter a more ambiguous space, in part through Dimple’s trajectory as an artist — and that of her heart. Photographer Dimple travels to Bombay to shoot the browns — or so I thought. As I spent more time there, though, to my surprise and delight, blue began to overwhelm — initially in terms of actual sightings of that hue in Bombay. And that hue became the clue, led me to the idea of exploring the ‘bigger’ blue: music, mood. The wild blue yonder. It was a liberating and dizzying approach — exploring this city with a theoretical map that simply had a splash of color on it. It required a kind of act of faith. So, like Dimple with her photography, my modus operandi — my unmapping map, if you will — while writing this book became this: To follow a color. All the way through. In loosening the coordinates in this way, I also fell upon what became one of the main themes of the book: the idea that there is no place like home…because home is not a place. It’s a sense of sanctuary — you may find it in a person, a place, a moment, a memory. We, as humans, are swimming cities; home is a direction.

Bombay Blues is, at heart, a story about home—the ways we seek and find and lose it all along the way towards it. How we inhabit, keep grabbing for it, as well as make and lose the habit of it. I think we all do this on some level our whole lives long. And so, this story, really, is for anyone—is our story, as ever evolving and shifting humans.

Besides being an author, you have now moved on to making music, what made you take up music?

Books and music have been a part of my life since I was a child. I began writing poems when I was about six, and often wrote melodies to them, turning them into songs, and then wrote two book length(ish) stories when I was in fourth and fifth grade. In my teens I was primarily writing short stories; I did some creative writing workshops in college and after as well. And during the post-university years—after a childhood spent in utter confidence I would one day be an author—self-doubt and insecurity (and endless distraction, AKA New York City) struck. I simply wasn’t sure I had enough of a story to tell—nor the ability to tell it even if I figured it out. I turned to music as an outlet in NYC. In a way, this was my more positive manner of avoiding writing fiction—it was a way of being creative without the isolation and long-term intensity/inward-turning that the discipline of novel-making requires. First I was in the recording project Wild Mercury, with Robert Dunn and Anthony Henin. A couple years later, completely bitten with the bug to be in a performing band, I answered an ad in the Village Voice and ended up getting the gig as lead singer in punk pop band io, with the brilliant Atom Fellows—who has remained my musical collaborator ever since (with him I wrote half of Bombay Spleen). When I moved from NYC to London, io was the hardest thing to leave behind—although in a sense I never did, given my uninterrupted musical relationship and friendship with the inimitable Atom (I’ve included a mystery band called io in Bombay Blues in homage of how we first connected; at one point they perform a song — “Light Years” — that Atom and I wrote together for Bombay Spleen; the music video will be out soon). In London, I soon joined a band called San Transisto, and through it met Marie Tueje, my musical sister and dear dear friend, with whom I wrote about half of Bombay Spleen as well. Music kept me in a creative space that I believe was vital for my fiction writing…when I finally got back to it. It was in London that I began work on my first novel, Born Confused. Though I did work/play with San Transisto during the writing process, mostly I was just focusing on the book. When We Were Twins, my first ‘booktrack’ album of songs based on Born Confused, came about as an afterthought, although an organic one; we didn’t record it until Born Confused had already been out two years. The writing process for both Bombay Blues and Bombay Spleen, however, was fully intertwined from inception to fruition: It took me three years to complete both—and they were finished within days of each other, during a very hectic NYC April spent in-studio in Brooklyn with producer Dave Sharma by day, and doing my final book pass for editor David Levithan by night. All along the way, each form helped me to dive deeper into the other — both lighting paths to arrive at the story.

Who are your literary and musical influences?

I don't know if the following artists are influences (would be nice!), but they are certainly inspirations: For her books and music: Patti Smith. Some long-time literary loves: Dickens, Balzac, Haruki Murakami, Milan Kundera, Emily Dickinson, James Cain, Judy Blume. Francesca Lia Block. Stephen Chbosky. Also love: ThrityUmrigar, Meg Wolitzer, James Cain, Marina Budhos, Nick Hornby, Raina Telgemeier, Zachary Lazar, Vikram Chandra, Coe Booth, Junot Diaz. Next on my reading list: Mud Sharks by David Barbarossa, Being Mortal by AtulGawande, and more Meg Wolitzer. Musicians I love: State of Bengal, PJ Harvey, Atom Fellows, David Bowie, Marie Tueje, Serge Gainsbourg, Dave Sharma, the B-52s, Jon Faddis, Joni Mitchell, Suzanne Vega, Kate Bush, Stevie Nicks, Cat Power, Arcade Fire, DamonAlbarn. Most recently played on my iPod: Mother, Mother; Courtney Barnett; Robert Plant and the Sensational Spaceshifters; First Aid Kit; Roisin Murphy. Also I must note that many of the musicianshomegrowing their sounds in India have served as one of the sparks for me, for one vital vibrant layer of this complex and creative city, that helped fuel my writing journey. Many are mentioned in Bombay Blues—and of course, this is not by any means a comprehensive list—including acts such as Sridhar/Thayil, Dualist Inquiry, Menwhopause, Shaa'ir + Func, Bhavishyavani Future Soundz, Kris Correya, Indus Creed, Sky Rabbit and The Raghu Dixit Project. Diasporically homegrown acts are mentioned as well, such as DJ Rekha, DJ Uri, State of Bengal, Talvin Singh, Anjali, Asian Dub Foundation. Karsh Kale is present in spirit (I named my fictitious character Karsh after him). And since the writing of the novel, I’ve been hearing still more sonically super stuff, such as Suman Sridhar’s recent solo work, Sandunes, and Your Chin, MC Kaur, Driving Lolita, Shiva SoundSystem, Still Dirty (whom I had the pleasure of playing with at The Zee/Jaipur Literature Festival this January, where I was doing book/album events), and Nikhil d’Souza (who is currently working with Nashville’s Jeff Cohen, my collaborator on the Born Confused theme song on When We Were Twins).

Bombay Spleen is a collection of songs based on your book Bombay Blues. What are you trying to connect using both mediums?

Together Bombay Blues/Spleenare my kind of ode to the mother lode. I knew from early on that I wanted Bombay Blues to have the feel of a piece of music (the book is an exploration of the blues on many levels, including the musical sense, too—but the joyful tones too). Likewise, I wanted Bombay Spleen to have the feel of a story—and to not only create an arc that would parallel the heroine’s journey in Bombay Blues, but also one that would trace (not necessarily chronologically) the story of Bombay itself, from its beginnings as seven islands later reclaimed to become the city we know today.

Bombay Spleen opens with “Catherine”, an ode to Catherine de Braganza, the Infanta of Portugal, whose dowry to Charles II was the islands that became modern-day Bombay. It’s the ‘beginning’ of the story in this sense, a birth of a version of the city (the album bookends this with track “Lady Liberty”). The Spleensongscape—and book landscape-- include Bombay settings Chor Bazaar, Juhu Beach, Mount Mary, Colaba, Mahim, Mazagaon, Parel, Old Woman’s Island, Chuim Village, Union Park, Lands End, Worli Fort, Reclamation (and even NYC and London) — and Heptanesia. And the crossfeed with the book was/is constant: Bombay Blues itself is embedded with lyrics from Bombay Spleen; sections are written directly in poetry, and it ends with double codas: a poem about the browns of Bombay, and one about the blues.

As well, music is a main theme in both my books: how it brings people together, as a universal language, as well as the way it transforms with culture and chronos, moves its grooves with the diaspora. It’s also what some of the characters actually do and are pursuing (both novels are populated with DJs, musicians, producers, nightclubs, live music). So it felt fitting that this would be a musical story with a storytelling soundtrack.

Can you tell us something about the genre you are trying to promote 'booktrack'?

I see it as expressing a story, just from different angles. The prose, the music, and now, with the music videos, the visual angle too. My first booktrack, When We Were Twins, is an album of original songs connected to my first novel, Born Confused (it released two years after the novel came out and was featured in Wired Magazine for being the first ever ‘booktrack’, which was lovely). With Bombay Blues and Bombay Spleen, the prose and songs developed organically side by side; I don't recall it being a conscious decision so much as a natural way for me to explore and express the story, as books and music have been a big part of my life since I was a child, and as an adult (grown child!), I played in bands in NYC and London for years, too. Although Bombay Blues and Bombay Spleen can be read/heard independently, for me they’re one tale relayed across multiple media.

What would you consider yourself more of - an author or a musician?

A person telling a story—no either/or. It’s just that one version of the story is audible. In Born Confused (and on When We Were Twins) Dimple learns that a hyphenated identity doesn't mean that you're 50-50, half of each. You can be 100-100. Frock, you can be 200-200. With Bombay Blues/Spleen, I wanted to move beyond ‘either-or’…and even beyond ‘and-and’. For we are always much greater than the sum of our parts. The city we live as humans is multiplicity. A hyphen doesn't have to be a border: It can also be a bridge. And for me, Bombay Blues –and Bombay Spleen--is about walking this hyphen, existing on that bridge — not on either side of it. It may be, in fact, by inhabiting this in-between that we finally ‘arrive’. And that’s the space—this zone of blurred boundaries—that I’m drawn to creatively as well.

You have two albums and two books released so far. How has the journey been?

Challenging, invigorating, exhausting, blessed.

Where do you get the inspiration for your music and literary works?

Once the seed of the idea makes itself felt and you surrender to it, you’ll find inspiration in the cracks on the sidewalk. In any and everything: film, photography, art, music, yes…but also in the tiniest daily human interaction, the weave of streets, and (a big one for me!) on public transport—subways, trains, buses. For me, more than anything, inspiration comes from people—both real and really imagined. Family history..And places—both real and mythical, too .Born Confused is in many ways my love letter to New York City; Bombay Blues to Bombay. And one huge thing I’ve learned: Inspiration is a habit; you don’t need to wait for it to get to work. You can’t wait for it: The work itself provides the inspiration. You don’t need it to write; rather, you often need to write to experience it, find it. And, once you do, nurture that flame with the utmost care. It will give you sustenance for the journey—and remind you of why you set off on it to begin with.

What is the music scene like in the UK?

Splendid! Recent gigs I’ve been to include Patti Smith, Damon Albarn at Royal Albert Hall, Driving Lolita and Arrows Down. Next up will be Happy Mondays. Much of my favorite music has come out of the UK—whether it’s by UK artists or others who were just more avidly embraced here first. My top music show is Later…with Jools Holland (India’s Raghu Dixit Project has played on it!). And the late 90s UK music scene provided a still burning spark for my writing path, with artists such as State of Bengal, Asian Dub Foundation, Joi, Anjali. But I don't know if there is such a location-specific scene anymore—given the role of technology, travel, and the crosspollination this has resulted in. Just as with the diasporal landscape—it’s getting harder and harder to limit the people in the diaspora to the country that they live in. To define them by their geographical base. Ocean-crossings occur constantly now –whether by flight, or Wi-Fi. In 2008, for example (after a decade away from India), I’d made a very short trip to Bombay to see if it would spark an idea for my second book. The one night I went out (I was ill the other days), I ended up at Zenzi—my only time in this legendary space, but enough to make me dedicate a section of Bombay Blues to it— and met a few people who are still fixtures in the indie/alternative arts scene in the city today (such as Monica Dogra and Randolph Correia). That night, out and about in Bandra, I just kept running into people from NYC; it was disorientingly exciting for me to discover this kind of modern and personal ‘hook’ into a city that had always existed primarily as one of family history and myth-stery (this was the first trip I’d ventured out in Bombay as well; previous childhood visits were always spent entirely with my grandparents in Powai, then my relatives in Varad). This whole experience sparked something: For the first time, I got the sense I might be able to work my way closer, find a new kind of portal into this in-my-blood yet ever elusive city (though I didn't actively begin work on the book until a couple years later). The same running into people occurred during all my research trips to Bombay over the course of 2011-12. And just this January, at my book/album launch at Café Zoe in Lower Parel (curated by Sweety Kapoor/The Solo Session), the room was peopled in part by folk I know from NYC and London (and even Paris!). Lately, I find I’m always using the word ‘here’ for…everywhere—no matter where I am. At Café Zoe alone, depending on whom I was taking to, I was saying ‘here’ to indicate NYC, London— as well as the very Bombay space we were in. A kind of lovely luxurious disorientation.

Can you tell us something about your early days of growing up in the US and how books and music influenced you and how you took up these professions.?

Really, with Born Confused I wanted to fill a hole that had been on my childhood bookshelf, with a South Asian-American coming-of-age story. An exploration of ‘brown’. (And, many years after that, one of the reasons I wrote Bombay Blues—an exploration of ‘blue’—was to move beyond the skin.) I grew up in a small, predominantly white town in western Massachusetts. We were the first ‘brown’ people—South Asians—there, though there were a couple of African-American families. At that time there were no people of our particular colour anywhere: on bookshelves, in bands, on T.V., even forecasting the weather. (Add to that the fact my parents were the first from both sides of the family to immigrate to the U.S.A.) Growing up, I was perpetually to be found with my nose glued in a book. I literally walked into walls sometimes I was so immersed in my reading. (My childhood favorites—Enid Blyton, Dickens, Nancy Drew— all have warped and yellowed pages from the bathwater hitting my shoulder and then them). Though I knew I wanted to be a writer from early on, I didn't think so consciously about performing music in those days. However, I used to spend eons inventing band names, singer names, album titles, song titles. I’d design the album art for these imagined crooners—and sometimes even write the songs themselves (accappella; lyrics and melodies). I had a whole series of index cards where I’d draw these fictitious frontwomen on the front and write out their bios on the back. Always women. Always frontwomen. And all of them—each and every single one, I’m realizing now: always white. Amazing, when I think now, that I never ever pictured myself singing the songs I was writing, incorporating into albums, designing the art for. Which I guess says something about the environment I was growing up in. Really, this was my main struggle as a writer: doubting whether I had what it took to write a novel. Utter confusion about what to write, how to express my cultures. In short: not recognizing the value of my own story. That, though I’d never fully felt a part of either side of my hyphen—Indian-American—that was a part of being part of it. I’d realized at some point in NYC that I wanted to write an Indian-American story—but felt I wasn’t Indian enough nor American enough to do so. One heart-pouring night in the East Village out with a friend, I was lamenting this fact to her when she turned to look me straight in the eye and said, “That’s your story.” It was a pure lightbulb moment: It had never occurred to me to consider my hyphenated identity as—rather than a neither-here-nor-there space—a You Are Here. A world, a way, a tale in its own right. It took a few years for me to know what to do with this epiphany though. And during my own NYC years of confusion (about career, culture, love, life, which subway line to take….)—and avoiding my novel (or, more positively put, gestating my first book), amongst other things, I worked several jobs as a copyeditor (which—though at the time the serial comma often risked sending me into a coma—has turned out to be a great skill for cleaning up prose and songs alike). I also interned at The Paris Review, hostessed at a Tex Mex restaurant, worked as a secretary (unfortunately, for my coworkers) in the Whitney Museum’s Film & Video Department, walked a saluki (who one day escaped me and sent me on a 100 mph chase through Central Park), co-hosted an online streaming music program, and party promoted at a nightclub—all this while collecting course catalogues and contemplating my escape from it all by going to grad school (really, an escape from writing that book!)…though I could never figure out for what. I also joined bands, took an intensive filmmaking course and made two short films, and continued on with creative writing workshops…but couldn't work past several connected stories with a white protagonist who—with very little maneuvering, actually (hitting Find/Replace for the most part) — turned Indian-American along the way. (One day, a few stories in, a couple fellow workshoppers asked me why she was Amy from Minneapolis when her POV was so clearly from a kind of ‘other’ vantage point; till then it had never occurred to me I could make her ‘brown’.) On some level, up until that point, I’d always viewed most of the jobs I’d had as obstacles to the path I was meant (I hoped) to be on. But as a writer (well, as anyone really!) you can turn that obstacle on its head and discover a portal. What’s wonderful with storytelling—whether through fiction or music—is that any experience is still an experience, and you can learn to value it as fodder. That’s not to say there weren’t moments where I wondered if I was getting a little too into the fodder and not enough (or at all) into the fiction. But ironically, and wonderfully, the very confusion I felt during my years in NYC—my most lost moments of all—ended up being the catalyst and unremitting spark for Born Confused. After all, a little confusion’s not a bad thing. It makes you question things. Reassess. Reinvent. Turn the Confused to Creative. I actually sold Born Confused on a proposal before having written it. It’s a serendipitous story: I met David Levithan, the man who would become my editor through the violinist in the punk-pop band I was frontwoman in at the time in N.Y.C., when a group of us went to see Fiona Apple play at Roseland. We hit it off, though we didn’t talk books at all that night—just music. A couple of months later, when I knew I was moving to London, I set up a meeting with David at Scholastic to see if I could rustle up some editorial work so I’d have something to do, could hit the ground running in the UK. Unbeknownst to me, David was just about to launch the Push book imprint, and within moments of my arrival, said: “Perfect timing! So what’s your book idea?” Somehow I knew it wasn’t the moment to say: Um, I just want to proofread someone else’s book. So I told him a truth: ‘Well, I’ve been working on a South Asian-American character’s journey through my short stories and would love to tell that tale in a novel.’ And David said, ‘Well, that’s a book I’d love to help you get on the bookshelf. So get to London. Unpack. And send me a one-page synopsis.’ So I got to London. Unpacked, and unpacked my idea as well: I sent that page. He liked it. And then, a few months later I’d delivered a final proposal that consisted of a twenty-five-page outline of the action (for which I used what I’d learned in a screenplay writing course in terms of structure), about fifty pages of my short stories, and a couple scenes from the proposed book. And Scholastic bought it, which was very exciting. It was a bit unusual to sell a book on a proposal like this, and it helped me immensely to know there was someone out there waiting for it. And what an incredible experience it’s been to find that Dimple’s story seemed to resonate with so many people once it came out. It was thrilling for me that Born Confused was recognized as the first ever South Asian-American coming-of-age novel, but equally thrilling was hearing from readers from all kinds of backgrounds and ages who’d connected to Dimple Lala’s journey. In fact, I often hear from non-South-Asian readers telling me, “That’s exactly my life… except the food is different!” (Though there is a possibility this isn’t true, especially if they’re Italian in part. My mother can make a mean spaghetti bolognaise. But then, maybe their father makes a memorable pakora…)

Do you have family back in the UK.Does literary and music run in the family too?

Not immediate family –these beloveds are largely in the USA and France, and India too--but a friendship family, yes. And though my parents and brother are all physicians—yes, it does run in the family (and my parents have also been the very first readers of my first epic drafts on both my books—and among the first listeners of every incarnation of the songs on the albums, too; they have been a huge source of support and encouragement my entire life). My GP mother sang on the radio as a young woman in India--but was discouraged from pursuing the arts for their impracticality--and is a wonder with a pencil and sketch pad; my cardiologist father is a wonderful writer, and since his retirement has been drawing a lot and teaching himself piano, too; my brother—a neurosurgeon who was a huge influence on me growing up, introducing me to Patti Smith, Kate Bush, the B-52s, Milan Kundera, Gabriel Garcia Marquez--plays guitar and piano, is a gifted writer, and has written songs as well (including one of the tracks on When We Were Twins, “Generations”). Growing up there was always music in our home—my mother singing in the kitchen, segueing smoothly from The Carpenters to “MithiMithiBaaton Se” (now this was a diasporic remix if ever I heard one!)…just as she segued from making spaghetti for my brother and me to khichdi khadhi for my father. My brother was often on the piano (Led Zeppelin, Chick Corea, Steely Dan). My father humming along to all of it. Our kitchen had a Krishna temple. My bedroom: a Prince poster. My brother’s: The Eagles. Our living room: Kashmiri carpet. Our basement: a stereo and strobe light. And books, books, books.In nearly every room. And the next generation is looking to contain several book and music lovers as well--two precious members of which are on Bombay Spleen: My older daughter sings “The Bombay Blues /MerMary Scat”, with my little one providing a wee backing vocal!

Interviewed by Verus Ferreira